Lisa’s Story

Lisa’s Story

One of the questions that a person living with epilepsy is always asked is “what is epilepsy?” Epilepsy has been defined as a chronic neurologic disorder of the brain, and according to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 50 million people worldwide are living with epilepsy. While it is not contagious, there has been a lot of social stigma around this disease. It is characterized by episodic seizures and the causes include but are not limited to brain damage from prenatal injury, congenital disorders and abnormal brain development. A seizure is a sudden surge of electrical activity in the brain. Seizures can cause strange sensations, emotions, and behavior. Seizures can also cause convulsions, muscle spasms, and loss of consciousness.

Explaining Epilepsy

While this is the scientific definition I am always faced with how to simply explain what epilepsy is – something that I have struggled my whole life to understand. With the social stigma, I have come up with a definition that is less demeaning and easier for the public to understand. To me, epilepsy is simply ‘fighting you for you’. I have chosen this definition because this is what it feels from personal experiences. During the seizures, the pain is so intense and real, and I fight for it to end, but the more I fight the more prolonged it is. The medical experts say “you should let the seizure take its course” but that is easier said than done. I say ‘fighting you for you’ because on several occasions I have to fight different factors that may possibly cause epileptic seizures. These factors range from diet change, to being emotionally hyped, a change of environment, an infection, a simple pollination of flowers, the anti-epileptic drugs, and the most difficult for me as a woman is the unavoidable monthly cycle among others.

Early experiences with epilepsy

My first seizure happened when I was still a baby but doctors told my parents that it was a convulsion. They said that I would grow out of it when I got to a certain age. Well, that did not happen and in fact the seizures got worse so I was put on medication. From when I was around 8 years old, my family moved a lot due to my dad’s different work postings. We eventually settled in Zimbabwe when I was around 11. I had a neurologist in South Africa who monitored my progress and said I was fairing on well, and the prescriptions for my anti-epileptic drugs reduced but somehow my health deteriorated again. The truth is this had both a physical and psychological effect on me and I felt like yet again I had failed in accomplishing a goal. The seizures were getting the best of me physically. I was getting emotionally bullied in school and this had its fair share of negative effects on me psychologically. I decided that going to school was not an option for me because it was a reminder of my abnormalities.

The social burden of epilepsy

My parents were able to somehow convince me to go back to school. According to research, people with epilepsy feel stigmatized by their conditions. Further evidence from research, show that the stigma correlates with anxiety, depression and low self-esteem. In school I had no friends because people thought it was contagious and that I was bewitched. I went through high school feeling and being lonely with just a handful of friends who to some extent understood my condition. It is hard up to date to live with epilepsy because people are unfortunately still uneducated on the matter. We moved back to Kenya, my home country in 2013 where I finished high school studying under the Accelerated Christian Education System. The stigma of living with epilepsy back home in Kenya was the same as in Zimbabwe. The reaction from my fellow students was the same and so was the treatment. I joined university in 2017 and I was determined that it was a fresh start for me. No one knew of my condition and therefore I fitted in nicely.

Epilepsy in college

At first I was very reserved and introverted but as time went by I became fairly out spoken. With my determination of being “normal”, and not sharing my condition with anyone, the first one and a half years of university I would occasionally get sick and have serious injuries. I had and still have encounters with lectures telling me I ‘faked’ my condition as an excuse for missing classes or not do exams. Some lectures put me in compromising positions and with my refusal to their expectations; there was a price to pay hence being graded unfairly on some occasions. Due to the prolonged use of the AEDs I had and still do experience memory loss issues – something that people with epilepsy experience as a side effect of the drugs but of course the severity is different for every individual. On some occasions they also said that I understood concepts slower than the rest of the students, which is another effect of people with epilepsy. Soon after, my condition was known to people around me at the university and of course they asked questions. My friends were helpful when I had the seizures and would put in the effort to make sure I got the necessary help but as time went on even they had enough and slowly started to leave. The medical team at the university was and is still helpful when called upon.

I am in my last year of University and honestly I have been through a lot and may not have the same amount of people in my life as when I started, but through those experiences there are positive factors to take from them. I still get the seizures but living well with epilepsy is a goal I hope to achieve. I am working with my neurologist to see what anti-epileptic drugs work best for me. I recognize that the medical experts can only do so much and it is upon me to do my part.

My 4 tips for living with epilepsy

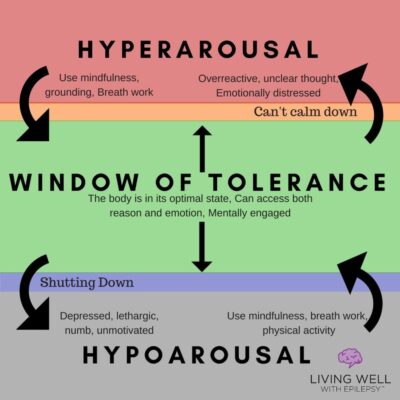

1. Physical activity can help

Stress is a major problem for me. I can’t live with it and can’t live without it. In order to be able to control stress and minimize “spin cycling” in my mind, I have a list of do’s and don’ts to help me cope better with stress. I do this by engaging in physical activity and noticing when I am tired and allowing myself to take a rest.

2. Find work arounds for memory issues

Memory loss (brain fog) and short concentration span is another problem for me and for that I try having sticky notes and phone reminders to try curb it. Eating right also contributes a whole lot when it comes to mental clarity. A healthy diet is beneficial both physically and mentally.

3. Have a seizure response plan

Having a seizure pre-, during, and post plan is key because it helps the people around you to know what to do and not to do. Having a support system of family and friends is crucial because you don’t have to worry about being in safe hands. You can do this by informing the people who are around you what to do if/when you have a seizure; it serves as a first aid guide as well. Having an epilepsy diary is great so that you document what type of seizure it was, what happened during the seizure, when it happened and a lot more. This makes it easier for your neurologist to have better diagnosis.

4. Communicate with your neurologist

The most important thing to do is communicate with your neurologist. It is important that you let them know how you are faring, and how your AEDs are treating you because there are many other modes of treatment. If you feel the neurologist is the problem then change them, and never self-medicate as the interactions may have negative effects.

Lisa’s personal experience

Am not an expert but these are just personal experiences that I am sharing with hopes that they will help others and let them know that we all have a story to tell and we are perfect in all our imperfections. Even though I may feel like a burden because I get seizures and can’t do some “simple” things, I am reminded that every person is differently abled.

Lisa Kiarie is founder of the Lisa Kiarie Epilepsy Foundation. To learn more about her efforts you can find her on social media at https://www.facebook.com/lisa.kiarie.9.

Leave a Reply